Marilyn Manson Changed My Life

An excerpted chapter from a forthcoming music book, on the occasion of a comeback.

I have to take one step back before getting into the Marilyn Manson phase of my teenhood because I was aware of Manson—and a casual listener—for a couple of years before this phase began in earnest. I was introduced to Manson in the most cliché manner possible, and one that I’m sure would make Manson himself proud: through religious forewarning.

It happened at yet another Catholic Youth Group at the end of 2007. This one was neither CYO nor the Legionaries of Christ, but another homeschool-oriented organization much closer to the latter in temperament. The frontman of an Irish-Catholic rock band came in to deliver what, to his credit, was a far more nuanced and reasonable message than most children in the same position receive: Rock N’ Roll was not inherently evil as some fire-and-brimstone preachers might suggest (The Beatles, Pearl Jam, AC/DC, and even Metallica were all OK in his opinion) but rock and pop-culture in general could be powerful tools of the Devil, and so one needed to be vigilant and critical about what one was taking in. He emphasized how listening to heavy stuff could be a slippery slope and said that he now drew the line sharply after Metallica, having gone too far earlier in life. “I used to listen to Marilyn Manson,” he said, “no joke.”

Little did he know, his words would change my life in the opposite direction of their intent. I had thought Slayer was the heaviest and most evil band in the world, having been forbidden by my father from playing “Raining Blood” on Guitar Hero 3. Who was this female solo artist, with a glamorous-sounding name, who was supposedly worse? I looked Marilyn Manson up on iTunes when I got home and realized I was familiar with two of his songs: “The Beautiful People” and his cover of the Eurythmics’ “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)”. True to his supposed wickedness: both scared the shit out of me whenever they came on the radio. Now I could put a ghastly face with the music.

I didn’t hang around Manson’s iTunes page long enough even to realize that he was not, in fact, a woman. But even this brief exposure to the pop virus “Marilyn Manson” gave me a terminal case. I was drawn back to Manson over the ensuing months and years with the kind of pull that comes only when something has been demonized as the ultimate forbidden fruit. I moved quickly from dark fascination to apologia, from “I can’t believe how fucked up this guy is” to “he can’t be that bad right?”

It was YouTube interviews that drew me deeper in. In these videos, Manson sounded intelligent, sensitive, and maybe even shy: someone just like me. I learned the difference between theistic Satanism and atheistic Satanism, and that Manson didn’t necessarily consider himself even the latter. Rather, he was simply critical of organized religion and had a flair for performance. I was getting more and more comfortable with the music and downloaded his 2004 greatest hits compilation Lest We Forget: The Best Of. As for his controversial viewpoints: his arguments against Christianity did kind of make sense. At 14 I was just dipping my toe in, but my fate of spending the next half-decade as a Reddit-tier atheist was all but sealed. This—like other elements of Manson’s influence upon me—is a dubious legacy, but undeniably instrumental in terms of my overall development.

It was February of 2010 when I became a more serious Marilyn Manson fan, and I remember it with the clarity of a conversion experience. As with conversion experiences and epiphanies in general, it seemed to come from nowhere, though I guess more technically it was the moment when several existential and spiritual threads that had been building unconsciously for months made themselves known, lighting a new path forward. But don’t worry: If this were only the story of how Marilyn Manson became my favorite musician, then I wouldn’t be telling it. Certainly, Manson did become a singular obsession, but the conversion was not merely to fandom but to something much larger and longer lasting: the life of the mind and the life of art.

Why were philosophy and creativity tied inseparably to Marilyn Manson in my head? It’s hard to say. Manson was far from the only potential intellectual and artistic influence in my life even then, and he would be swapped out with other, ostensibly more mature influences before long. But for some reason he was the one who made something click for me, snapping me out of a certain suburban nihilism and making me more ambitious and excited about life. Estimations of Manson as an intellectual, an artist, an esotericist, and a human being all vary widely. I’ll save most of my apologia for later but let me say: even if Manson is as mid-witted, drug-addled, confused and/or morally execrable as some suppose, he was playing with powerful ideas in his music that transmitted to me with a beautiful clarity. He became for me what older Kabbalah and Nietzsche-obsessed artists—most notably David Bowie—were for him: a potent inspiration to evolution and self-overcoming.

In February of 2010 I was 4 months into the first relationship of my life and ill-equipped to deal with the issues that were arising. I felt trapped by my girlfriend’s neediness and had a sense that there was a gap between her view of me versus who I actually was. In an adult relationship, you can work through some of this stuff, but this was not quite an adult relationship. My girlfriend’s fear of abandonment and other imbalances were well beyond anything I was going to be able to help her deal with, still being on the path to emotional maturity myself. I didn’t necessarily want to be with anyone else, but I craved being single and feeling normal again. Yet my girlfriend had grown so emotionally dependent on me so quickly, that I feared what a breakup would do to her.

One example of how I was different from what my girlfriend wanted me to be had to do with the subtleties of music, aesthetics, gender, and subculture. Her notebooks were filled with sketches of Emo boys with jock-builds and six-pack abs: her idealized balance of sensitivity and masculinity. I wanted to be weirder—and frankly faggier—than that. She wanted Emocore, I was becoming more and more of a Scene Kid. I liked the aesthetics of Screamo and Post-Hardcore, but she got much more exclusively into these genres than I ever could and developed a deeper emotional connection to them. Meanwhile, I cultivated a secret love of Jeffree Star, Blood on The Dance Floor, Brokencyde, and Dot Dot Curve, probably as much because I was repressing my inclination to listen to Pop and Rap music as anything. I wanted to incorporate more and more colorful items into my wardrobe, with no regard for if they were from the men’s or women’s section—a Hello Kitty hoodie, neon-green Converse, a purple kaffiyeh, you name it—and she consistently guided me back to darker colors and fitted but masculine cuts.

I’m not saying my girlfriend wasn’t totally reasonable in what she wanted from a boyfriend. When I say she was insecure and emotionally damaged, it isn’t because she didn’t want to date a flagrant metrosexual, but rather for other issues that went on behind closed doors and over hours-long phone calls. I’m talking about frequent sobbing and shrieking, and stern, monopolizing demands over my time taking me away from family and friends. I’m talking about threats of self-harm and suicide used to manipulate me to do things and go places that got me in trouble or caused me to fall behind in school (which, just as a reminder, was still totally online and self-paced). She certainly had her issues; I only mean to admit that my attraction to the Scene Kid thing proved I had mine as well.

I’ll stop short of saying that “Scene” was an inherently toxic subculture— like others, I certainly have a degree of nostalgia for it now—but I don’t think it’s a coincidence that so many representatives of it turned out to be narcissists and abusers of the worst variety. It was an image-obsessed, ultracompetitive peacocking subculture wrought by the hot-house environment of Myspace: whoever could tease their hair taller and wear the most outrageous thing would garner attention and respect. Emo had its issues, but at least it was also about music and collective catharsis. Scene was almost exclusively about likes, clicks, and narcissistic supply and in this way—like its vapid music—was ahead of its time in all of the wrong ways.

My attraction to the Scene subculture had to do with my bottomless need to be seen and admired. Somehow this need had not quite been sated even with a girlfriend and a friend group filled with other female admirers. I became even more obsessively vain, spending hours in the mirror, wanting to push the envelope more and more. In fairness, maybe I also leaned into the subculture due to my feelings of being trapped in my relationship. Disappearing into vanity, elaborate hair styling and the clearance sections of mall stores was still something I had control over even as my girlfriend encroached upon everything else. And maybe if I leaned into this increasingly queer-coded behavior my girlfriend would distance herself, solving the tricky bind I felt like I was in relationship-wise.

This little detour into the Scene subculture circles back directly to Marilyn Manson, believe it or not, because it was a representative of this subculture that got me to listen to him with new ears that fateful February of 2010. I was Facebook friends with what I think was a non-fake Jayy Von Monroe1 profile, and he posted something about how Mechanical Animals was Marilyn Manson’s best album, using words like “Warholian” that appealed to the burgeoning cultural critic in me. Maybe heavy music could genuinely be art. Maybe it was time to move on from the compiled tracks on “Lest We Forget…” and listen to a Marilyn Manson album for real.

Though I got further into Manson through Jayy Von Monroe, Manson’s influence would soon sublate Scene entirely for me. Meaningfully: one of the first things to change—to my girlfriend’s horror—was my hair. It was still black and I’d still back-comb and spray it, but in an act of intense rebellion against my former self, I would not straighten it, instead cultivating an (artful, I thought) rat’s nest inspired by Robert Smith2. Manson himself was the biggest influence behind my new aesthetic, though: embracing genderfuck, eyeliner, and alternative fashion styles now for the sake of shock—even ugliness—rather than admiration (this was a necessary step away from Emo/Scene for me, but I’m glad that this phase, too, only lasted a few months). On a more philosophical level, I’d find internally in Manson-inflected individualism the intensity and confidence I was seeking from the Scene subculture with its outsourcing of self-esteem to social media. This pivot—even during subsequent periods of my life during which I’ve held Manson at a healthy distance—has always struck me as being a move in the direction of relative maturity and wisdom.

The conversion experience I have hyped up happened quite specifically and suddenly while I was listening to the first track on Mechanical Animals, “Great Big White World”, on YouTube at my family’s desktop computer, the evening of Jayy Von Monroe’s Facebook endorsement. The dramatic synth riff gave way to a spacey intro and first verse—punctuated 47 seconds in by an oddly Zen keyboard breakdown—and I was hooked. It was like a vital message was being transmitted to me from the stars.

Having seen the title of the song on iTunes, I’d always supposed “Great Big White World” might be like Eminem’s “White America”: a politically conscious racial reference. This would have been on theme for Manson who shared with Eminem the status of being a cornfed-Midwesterner-turned-America’s-worst-nightmare, and perhaps the racial connotation is one of the layers of meaning behind Mechanical Animals’ constant references to whiteness. But what was actually meant by “Great Big White World” took me totally off guard and moved me profoundly: a world drained of all color, an ugly world without art or any kind of animating spirit, our world or something not too far in the future of our current trajectory, so I supposed. I immediately knew I wanted to be on the side of the color and the light: a color and light that had everything to do with art, but seemed quite far from my suburban, subcultural, dilettantism. Mechanical Animals came out the year before The Matrix and it is tinged with a similar pop, techno-Gnosticism3. Fittingly: it became my first red pill.

But what exactly was the target of Manson’s criticism with the album? Reviewers of the time were quick to point out that it wasn’t exactly clear, or that Manson was turning on the very entertainment industry that enabled his stardom. Realistically, the record’s thesis probably isn’t fully baked, or could be criticized for pointing out issues without taking much of a step toward their solution: the musical equivalent of bemoaning the draining effects of cocaine between lines. But certainly, the meaning of Mechanical Animals was intriguing and far more nuanced than the cartoonish anti-Christianity Manson’s purported message was commonly reduced to. There was a reference in “Great Big White World” to Christians praying futilely even though God was dead, but beyond that, the polemic was first and foremost against anything sapping humanity and creativity, be it in or outside the confines of religion.

In line with this new realm of thought, I would soon read about both communism and fascism having a sense that both extremes had something to offer to this arts-first aristocratic radicalism that was coming into view. But first and foremost, the “Great Big White World” pill was a spur to change within myself. I had become subsumed by vanity and vapid high-school posturing and was missing out on a whole universe of expression, and intellectual and artistic stimulation, or so I imagined. What had started as a genuine interest in alternative music, fashion, and lifestyle had become me slavishly copying others with as much conformity as any “prep”. As for my girlfriend and the broader friend group I’d made through anime club: I was meant for bigger things. It sounds brutal now, and I’m not saying it’s nice to abandon friends at any point in your life, but your peers define your horizons in high school to a substantial degree. I sensed that my friends were largely weekend warriors who would never leave the suburbs of Philadelphia and while I sincerely don’t think there’s anything wrong with this (at least not anymore), I knew it didn’t have to be the case for me.

The psychic shift was sudden, but the life changes would still take a few months to come together: a few months spent diving into every nook and cranny of Manson’s discography, not to mention every minute of every interview I could find with him on YouTube. A few months spent getting back into reading and art, going to used book sales with my father, and generally cultivating a fierce thirst for knowledge. Manson flaunted his own readership in interviews praising everything from Nietzsche and the Bible to Dr. Seuss. I was willing to start from the ground up on this quest for knowledge, so I started with Seuss and some of the other children’s books that Manson seemed to be obsessed with: Alice In Wonderland4, Charlie and The Chocolate Factory, and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. I bought Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil as well, though it would still be a few years before I could successfully glean philosophical ideas from primary texts, Camus’ tersely written Existential novella The Stranger being the one exception.

In a deep irony, this was all partially me remembering who I was. Part of the intention of my parents homeschooling me had always been to shelter me from the stifling influence of the many. My parents never put it this way, but in some sense, I’d always felt growing up like I was better because of this sheltering. I was of two minds about homeschooling back then just as I am of two minds about it now. On the one hand, there was a lot that I missed out on, and I probably will not homeschool my own children. On the other hand, it is probably good that my imagination and intellect were free to grow up on their own side of the fence, and I credit this fact with much of my creativity and independence of thought. Whatever effect “Great Big White World” and Marilyn Manson had on me, it was in part a call to get back in touch with the sheltered elitism I’d been brought up with, and the carefree sense of play that had abounded between my four siblings and me, shut away from the influence of cable TV, vapid trends, and the judgments of our peers.

I believe Marilyn Manson’s influence on me actually improved my relationship with my large, Catholic, family. I wonder if I am the only person on earth who can say this? The ways in which Manson and similar pied pipers of degeneracy and rebellion can influence teens toward anti-social ends are too obvious and banal to recount, but I will always vouch for Manson’s more playful, literary, and intelligent side and the effect it had on me. I was also lucky. My position in 9th grade was perfectly fine-tuned to maximize the positive elements of Manson’s influence while minimizing the negative elements. Being homeschooled, I was insulated from potential Mansonite friends to do drugs, crime, or black magic with, and instead had only the cultural and creative outlets available to me within my family unit.

These outlets were surprisingly plentiful. I had parents who took culture and education seriously, and even though I was more at odds with their Catholicism than ever, I realized they had their nuances and found new ways to relate to them. Suddenly it was cool that my dad was a Philosophy Professor because Manson was into Philosophy and I wanted to accompany him on his trips to the Philadelphia Museum of Art because Manson was into art. Suddenly it was cool that my mom read books and listened to The Smiths, The Cure, and Joy Division. I realized my parents were far more cultured and intelligent than my friends ever would be, and they must have felt like they’d regained a son who had been taken away from them for a year+, hiding behind Emo/Scene garb and performative teenage isolation.

I had younger siblings and had taken quite seriously something Manson said in an interview about how the artist had to cultivate a child-like wonder, or at least a Peter Pan syndrome. My youngest brother says his first memory of me—and one of his first memories in general—is from this period and involves us building a tower out of a stack of my parent’s old post-punk cassette tapes, and sticking Star Wars figures in it. Before this, he says, he can only remember being vaguely frightened of me. Thanks, MM.5

The trajectory of my teenhood up to this point, then, was this: I’d yearned to leave the nest to gain experience and social admiration, but initially been frustrated. After years of struggle, I’d finally gained the experience and admiration only to realize it was vapid, and instead wanted to crawl back to where I had started—my family unit—seeing it now with new eyes and appreciation. Somehow each step had been largely inspired and accompanied by music, and Marilyn Manson had brought this first cycle to a completion. The whole thing has a snake-eating-it’s-tale, outsider’s journey quality that was similar to Manson’s own self-mythologizing on his triptych of most famous and classic albums: Antichrist Superstar (1996), Mechanical Animals (1998), and Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) (2000) and this is part of what appealed to me as I delved further in.

I won’t try to summarize my take on the full triptych “plot line” here, but anyone interested can find what Manson fans have pieced together on various fan sights and forums. Under any interpretation: the story is of a cyclical evolution from insignificance, to stardom, to corruption, to ruin, and back to insignificance. The positive upshot of this plotline is perhaps that within it, creativity, humanity, and knowledge are valued over their opposites (as I gleaned by way of “Great Big White World”). Taken as a whole, however, the story is unavoidably grim and apocalyptic: not cautionary so much as fatalistic and Sisyphean. I suspect that the Manson of the late 90’s, if accused of nihilism, would retort that the ill-fate of his triptych’s protagonist was due to the world in its current form—the “great big white world”, not evolved past Christianity and whatever other vapidities—and that in a changed world, a more fruitful, less self-destructive order might be restored. Perhaps this is what is behind Manson’s ostensible destructive hatred of the world—at least in his 90’s output—and why esoteric interpretations of Antichrist Superstar detect dark workings toward a benevolent apocalypse: a changing of the aeons—and end to Christianity—not dissimilar to what the likes of John Dee, Aleister Crowley, Jack Parsons, and Anton Lavey had in the crosshairs of their own magickal workings.

Indeed, Manson’s triptych showcases nothing so much as his deep esoteric influences, from the archetypes and “Fool’s Journey” aspect of the Tarot6, to Kabbalah7, and—I think to a substantial and under-talked-about degree—the films of Alejandro Jodorowsky8 ,especially The Holy Mountain. Other cultural references—e.g to the assassinations of JFK and John Lennon (Holy Wood), The Man Who Fell To Earth (Mechanical Animals), and of course Jesus Christ Superstar (Antichrist Superstar)—play important roles in the triptych as well, but the fundamental storyline is grounded in these more esoteric sources.

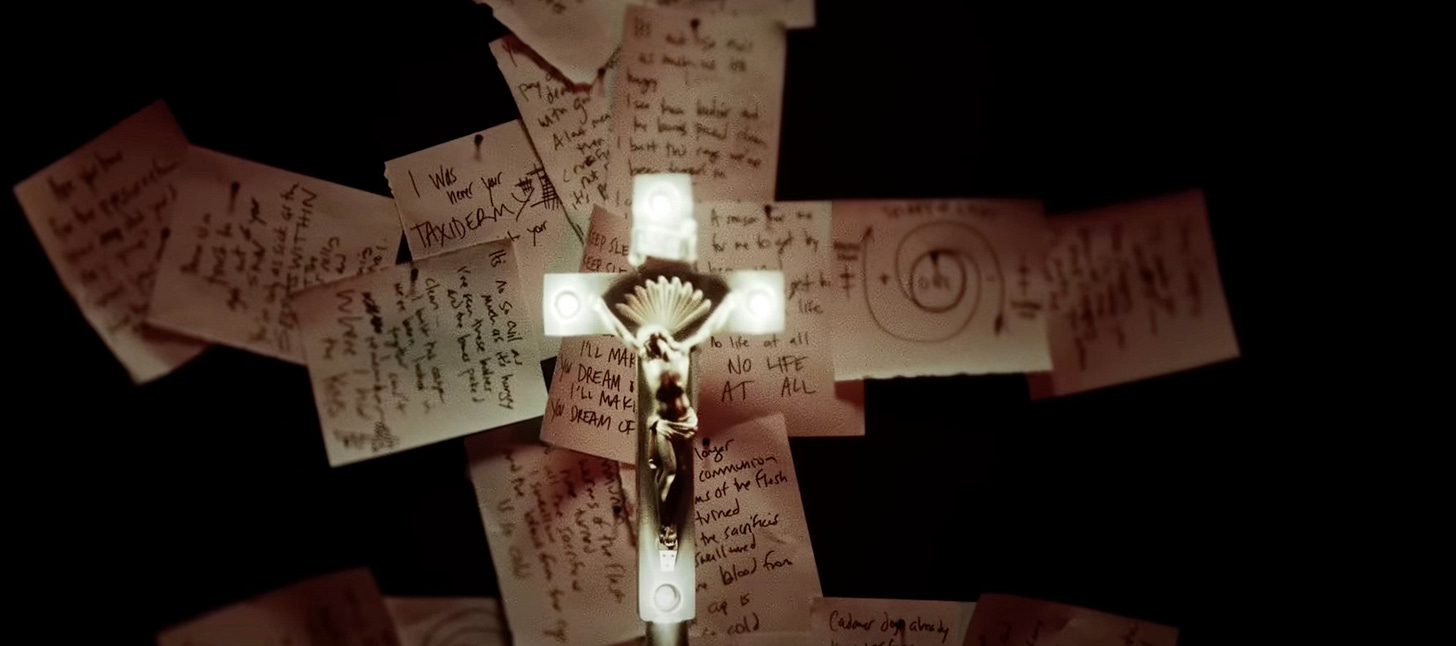

Perhaps the most illustrative and easy-to-interpret installment of the triptych is Holy Wood (In the Valley of the Shadow of Death), an album recorded and released during the post-Columbine crisis in Manson’s career, and therefore containing some of his most on-the-nose political commentary. Manson’s focus on the hypocrisies of the Christian right with their “guns, God, and government” running throughout the album renders it the favorite of many a certain kind of Reddit-tier Manson fan but a slightly lesser entry for me. I am sympathetic to the pressure Manson was under, following his scapegoating for the Columbine shootings by Conservative politicians, but hitching his star to Michael Moore talking points might be the aspect of his legacy that has aged the worst. Still: Holy Wood contains some of the most obvious highlights of Manson’s song catalog, and though the political themes are more topical than I prefer from my Rock N’ Roll, Manson delivers them in a way that is artful and clever enough to stomach, and this is where the Jodorowsky aesthetics tie in.

I felt I finally understood a key Manson influence years later when I finally watched The Holy Mountain, the first section of which contains satirical, psychedelic, horror surrounding the fetishization of crucifixes9 and guns, and their repurposing as consumer products. The movie takes place in a sick, parallel reality that looks quite a bit indeed like the sort of slipstream world portrayed on all of Manson’s triptych albums, but especially Holy Wood with its gun-cross lyrical and visual motifs. The name itself even harkens back to The Holy Mountain, with the use of the word “holy”, though in Manson’s case it is a double or triple entendre about media culture, sexuality, and of course the worship of the cross as a symbol and object.

To dive a little deeper in: the “In the Valley of the Shadow of Death” element is a reference to Valley of the Dolls: a film about the drugged-out exploitation of actresses in Hollywood that has more in common thematically with Mechanical Animals than Holy Wood, but that is obviously rich with symbolism for Manson in general, starring Sharon Tate, with her obvious connection to Manson’s namesake, for starters, and also containing a fictional cosmetics ad with the tag-line “The beautiful people use Gillian’s” that I suspect inspired the title of Manson’s most enduring song. Manson’s own “The Beautiful People” features a distorted sample of Manson family murder Tex Watson saying: "[We would] swoop down on the town. . . [and] kill everyone that wasn't beautiful".

You can rest assured that the irony of the Manson family’s deranged, fascistic fixation on beauty and fame in comparison with popular culture’s own obsession with these things was not lost on the young Brian Warner when he chose a stage name combining Charles Manson and Marilyn Monroe. At his industrial best—whipping up demented sound collage commentary on the American 20th century, with its hypocritical bifurcation of ugliness and beauty, sex and violence, etc.—Manson has things to say that you need only be interested in media theory, not necessarily a God hater, to appreciate. There’s a reason why David Lynch—himself an explorer of the darker side of American life but normally averse to anything properly “Satanic”—has collaborated with Manson several times. The implication I glean from Manson’s 90’s output is that if all of these disparate and contradictory elements of American popular culture were accelerated, the final result would be a force combining all—perhaps the antichrist himself—finding the ugliness in beauty and the beauty in ugliness, and dispensing with aesthetic and moral veils to reveal the occulted hierarchy and social-Darwinism behind all ( a take that is red-pilled in a fairly right-wing or at least thoroughly Nietzschean direction, I’d have to say). It’s still remarkable to me that Manson was able to explore such ideas via a mainstream record label. The resultant, vaguely plot-driven musical triptych is very slipstream and very Jodorowsky indeed.

“The Valley of the Shadow of Death” in the context of Holy Wood—much like the demented world in which the protagonist starts his journey in The Holy Mountain—is a land of weeping and gnashing of teeth inhabited by outsiders ("the Nobodies” in the album’s terms) who look with longing eyes over the mountain to Holy Wood. In The Holy Mountain, the protagonist escapes his origins and is trained in alchemy to enable his ascent of the titular Holy Mountain where—not to spoil it—but there’s basically a Wizard of Oz moment in which he (and the team of personified planetary symbols he has assembled) learn that there are no hidden secrets after all and that they had what they needed to complete the great work inside them all along. This is reflective of Jodorowsky’s atheistic mysticism and is more directly analogous to the kind of Jungian integration encouraged by typical interpretations of the Tarot, and within psychology. Manson’s “Holy Wood”, meanwhile, ends up being a land as corrupted and unhappy as his “Valley of the Shadow of Death”, and in contrast with the call to integration and internal change, is more diagnostic of a world that must be destroyed to be renewed: a more squarely gnostic vision10.

In a bit of forgotten Manson lore, Manson and Jodorowsky came very close to working together around the time of Holy Wood’s release. For a time, there were talks of Manson starring with Johnny Depp in a sequel to El Topo, or in a speculative gangster movie to be produced by David Lynch, but as is generally the case with truly interesting ideas in Hollywood, development didn’t go far. These film ideas were, however, soon swapped out for a movie version of Holy Wood to be penned by Manson and directed by Jodorowsky. Next, the speculative film became a speculative novel when Manson became gun-shy about the prospect of New Line Cinema altering his vision. Though the novel is unpublished as of 2024 outside of a single chapter, the manuscript is complete and has garnered praise from the likes of Chuck Palahniuk. Plot-wise, Holy Wood, seems to be an encapsulation of aspects of the triptych storyline written in the vein of William S. Burroughs or Phillip K. Dick and containing corollaries for such intriguing real-world figures as Walt Disney and Jack Parsons. It is a genuine shame this satire has never seen the light of day, as I suspect it would clarify quite a bit about what Manson was “really trying to say” with his 90’s output. Even Manson’s brief descriptions of the novel contain insights into his more personal interpretation of the triptych storyline, and perhaps some nuance on my foregoing, ultra-pessimistic interpretation of it:

The whole story, if you take it from the beginning, is parallel to my own, but just told in metaphors and different symbols that I thought other people could draw from. It's about being innocent and naive, much like Adam was in Paradise before the fall from grace. And seeing something like Hollywood, which I used as a metaphor to represent what people think is the perfect world, and it's about wanting — your whole life — to fit into this world that doesn't think you belong, that doesn't like you, that beats you down every step of the way, fighting and fighting and fighting, and finally getting there, everyone around you are the same people who kept you down in the first place. So you automatically hate everyone around you. You resent them for making you become part of this game you don't realize you were buying into. You trade one prison cell for another in some ways. That becomes the revolution, to be idealistic enough that you think you can change the world, and what you find is you can't change anything but yourself.

Holy Wood (the album) was released to critical acclaim, but lower sales than Manson’s previous two albums as the alternative/industrial 90’s gave way to the rap-metal early 2000’s, and this probably had some bearing on the waning interest of mainstream publishers and film studios in Manson’s ideas. The next 5-10 years would be marked for Manson by diminishing relevance and a midlife crisis that I will get more into shortly.

Holy Wood (the novel) would never be released but thankfully we have an entirely different, non-metaphorical book that fulfills the promise of telling Manson’s origin story: his autobiography The Long Hard Road Out of Hell (1998, co-written with Neil Strauss). I had no access to this book during the pinnacle of my enthusiasm for Manson, but I finally read it after finding it on sale at my college bookstore at the end of my senior year. Like all books Neil Strauss has crafted, the book is spectacularly entertaining, and far more insightful in terms of its sociological/philosophical content than would meet the eye.

If Manson’s triptych tells an ambiguous story of a will-to-power locked in a cyclical eternal struggle, then The Long Hard Road Out of Hell locates the kernel of real life it is all based on: “the boy that you loved”, to quote the final track off Antichrist Superstar, becoming the “man that you fear”. The true story is that of young, Gen-X, Brian Warner growing up amidst the suburban-American contradictions and hypocrisies of Canton, Ohio in the 70’s and 80’s: exposed in equal measure to fundamentalist Christianity, playground brutality, Saturday morning cartoons, and sexual perversion. He eventually moves to South Florida, starts a band, and assumes a persona that makes him a reflection of every dark and light, pleasurable and horrifying thing he grew up with. Parts of The Long Hard Road Out of Hell are sensationalized and/or disturbing, but I highly recommend it.

To return to my own origin story and Manson’s influence upon it: 2010 would become one of the strangest and most creative years of my life. The bulk of what Manson inspired in me was an ecstasy and a confidence, a genuine joy and sense of meaning to be found in the art life and the life of the mind. I took up watercolor painting and poetry, specializing in Manson-esque abstractions. My girlfriend was pretty good at drawing, but couldn’t understand my work: a huge problem to my mind at that time, almost as bad as the fact that we no longer listened to the same music. Initially, my plan of distancing myself naturally seemed to be working and it was my girlfriend who first brought up the idea of breaking up, after a freak-out regarding how much I was changing. This turned out to be a bluff on her end, and I had to harness some real coldness to finally bring the relationship to an end in May of that year.

I never talked to my girlfriend or the rest of that friend group ever again and retreated into solitude and creativity. Almost as soon as I had freed myself, I led myself to new cages: new romantic interests, new social identities, and new subcultural postures that I will cover in subsequent chapters. But hey: at least these cages were generally improvements on the previous cages, and how else can a free spirit evolve? In the meantime, I’d completed the first cycle of my young adult life, tasting several important forms of gnosis with Marilyn Manson as my guide.

I say that Marilyn Manson changed my life because even during the periods of my life where I have held him at the furthest distance for religious or hipster reasons, I would still have had to admit that the trajectory of my life would not have been the same without him. He started the trajectory of my adult life, in many ways, by initiating my serious interests in philosophy, art, and literature, and for this, I will always be grateful.

In 2024, the social hazards of openly being a Marilyn Manson fan are higher than they have been since at least Columbine, and quite possibly higher than ever. Certainly: Manson’s standing is dramatically worse within the entertainment industry and within urban/liberal enclaves than it has ever been: no managers, agencies, record labels, or TV shows dropped Manson after Columbine. The firing squad is no longer the Conservative right, but the #MeToo left, and though the sphere of influence of each of these sets of morality enforcers is completely different—and I can’t claim much first-hand memory of the supposed golden age of the Christian right—I am swayed by arguments that the left has always had the upper hand in terms of soft power. It’s one thing when Fox News and certain enclaves within middle America try to censor you (to the meager degree they can) but quite another when you are persona non grata to the rest of the media, the entertainment industry, academia, the art world, and basically just hip/fashionable company everywhere. Whereas the PR mechanisms afforded to the left side of the aisle quickly made the story of Manson and Columbine the story of conservative politicians scapegoating an outsider rather than dealing with trickier issues of gun control and mental health, it is unlikely that Manson’s reputation will ever recover from the current Evan Rachel Wood fiasco, even in the order of future events that goes as well as possible for Manson, involving a Heard-vs.-Depp style trial and total exoneration. If there is any saving grace in all of this for Manson, it is that the whole thing could conceivably give him his power back: no matter how amenable secular popular culture might think it is to a figure like Manson, he is at his best as an eternal outsider, in line with no popular gods or morality.

The irony of Manson getting canceled by the progressive consensus and the hip/fashionable world is that it happened at just the moment he was finally starting to gain real favor with such people. It was always cool to take Manson’s side versus the Christian right, but he was mostly viewed as a tacky outsider—a figure best appreciated by angsty teenagers—as opposed to a serious cultural icon. This was slowly but surely changing in the Trump era. Being a foil to Christian, middle America was regaining cachet, for one thing, but also Manson’s list of prestige TV credits was expanding, and a new generation of talents—like critically lauded rapper Lil Uzi Vert—were coming up and citing his influence. Manson’s final pre-cancellation album We Are Chaos was released on September 11thof 2020 and it deservedly garnered some of the best reviews of his career11. This was a few months after Manson did the ultimate in signaling progressive, in-group identity by posting—not technically the black square—but a Black Lives Matter banner on Instagram on the day of the George Floyd riots. I also recall an interview from 2020 involving Manson’s description of the devastating effects of the pandemic on his “mental health”, due especially to his limited opportunities to perform. This is reasonable enough, to be sure, but I remember thinking “damn, he’s really learning how to speak their language”.12

It all came crashing down in February of 2021 when Manson’s ex-fiancée—actress Evan Rachel Wood—posted on Instagram, detailing the years of horrific abuse he allegedly inflicted on her during their relationship. More allegations and civil lawsuits from several other women soon followed, following the typical #MeToo run of events. I don’t want to turn this essay into a rehashing of all these accusations, or Manson’s rebuttals, but the information is readily available online. I also don’t intend to dig my heels firmly in the sand of “defending” Manson against specific allegations. Make no mistake: I am rooting for Manson but for the most part, I’ll leave such defense to others.

A few general points only. 1) Evan Rachel Wood has established herself as an unreliable witness, to say the least. The most damning evidence of this involves an allegedly faked FBI letter13, and one of Manson’s original co-accusers withdrawing her lawsuit and claiming that she was manipulated into filing it by Wood and associate Ilma Gore14. 2) As with any #MeToo case, we can’t discount the degree to which such accusations may be opportunistic exaggerations if not outright falsities encouraged by the post-2017 climate. Evan Rachel Wood has already gotten her own HBO documentary out of the whole thing and a re-entry into the spotlight, so who knows? 3) Previous exes of Manson Rose McGowan and Dita Von Teese both confirmed (while still expressing solidarity with the accusers) that their own experiences with Manson did not match, and Evan Rachel Wood herself had previously spoken positively of their relationship, even years afterward. 4) The specific accusations are less often pin-pointable instances of sexual assault than patterns of generally sadistic and controlling behavior that—while shocking—are not exactly outside of the realm of what you might expect a woman interested in dating Marilyn Manson to engage in consensually or with something of a role-play mindset.

Naturally, the real meat of this case hinges on such questions of context: what was and was not “consensual”, what was and was not role play, and what was and was not a joke. Such matters will likely always come down to something of a gray area or a his-word-against-hers. As with the Heard vs. Depp case, I don’t necessarily think there is a clean innocent or guilty designation to be found here, and if it could be proved to me that all of Manson’s abuse and manipulation was as forceful as reported, I would change my mind. Obviously: I don’t know exactly what happened. I only posit that Manson’s claim—that everything he is accused of happened within a consensual context, and that to suggest otherwise is a “distortion of reality”—is worthy of consideration. And also: that from a legal standpoint the case against him seems extremely flimsy and will be hard to prove.

This issue of role-play versus genuine predation and maliciousness opens a larger discussion of Manson and how we should regard him. The dichotomy has never been easy to untangle. I am not saying Manson is above criticism in as far as he has always embraced darkness and destructive aesthetics—often blurring into genuinely dark and destructive behavior—but I do think he has always been entirely open about his proclivities, and that this counts for something. Opinion pieces following the accusations—e.g. from Rolling Stone—dubbed Manson a “monster hiding in plain sight”. But isn’t the response to this ‘no kidding’? What exactly can you accuse a monster of who has always been forthright about being a monster?

Bad stories about Manson have always followed him around, and often there has been ambiguity over their factuality and seriousness. The Long Hard Road Out of Hell details questionable and illegal behavior going back to Manson’s teenage years, including assaults, threats, planned homicides, sexual abuse, and smoking human bones stolen from a graveyard in New Orleans. But the book constantly blurs the line between fact, exaggeration, and pure fiction so that in most cases we are left to wonder. Manson has also been involved in numerous physical altercations over the years (the most notorious of which involved him allegedly pulling a gun on the editor of Spin for not putting him on the cover), and adjacent to a few untimely deaths and drug incidents, such as the passing of Jennifer Syme. Prior to the #MeToo accusations, Manson was largely given the benefit of the doubt, or forgiven on grounds of youthful indiscretion, but this has now all reversed.

The truth is, there is nothing in even the most lurid accusations against Manson that surprised anyone who had been paying attention to his lyrics and statements in interviews, especially from the 2008-2010 era. Maybe that indicts us all, but Manson’s love life had always been so thoroughly enmeshed within an intense, self-mythologizing, BDSMish context that none of us saw his self-reported behavior as something to raise questions about. We took the more concerning statements with a grain of salt—clearly refracted as they were through Manson’s notoriously fucked-up sense of humor—and assumed the others involved saw it the same way.

Case and point: in a 2009 interview with Spin, explaining his song “I Want To Kill You Like They Do In the Movies” Manson confessed to having “fantasies every day about smashing [Evan Rachel Wood’s] skull in with a sledgehammer” following their first of two breakups. This interview raised eyebrows when it resurfaced in light of the accusations, but Manson’s counsel was quick to put out a statement restating what was obvious to anyone who had read the interview at the time of its release: that the sledgehammer comment, “was obviously a theatrical rock star interview promoting a new record, and not a factual account,” and further that: “[t]he fact that Evan and Manson got engaged six months after this interview would indicate that no one took this story literally.”

In Manson’s case, as is so often the case with retroactive MeToo accusations—not to mention retroactive legacy considerations concerning whether someone was racist, misogynist, etc.—we are asked to throw away the cultural context in which the alleged wrong-doing transpired. Sure: by 2024 standards it’s unsavory to pursue a not-quite-eighteen-year-old actress in your late thirties. Sure, it would no longer be ok to make the sledgehammer comment even as a joke or to sell records. Sure, the other incident mentioned along with the sledgehammer comment—Manson calling Wood 158 times and cutting himself with each call—is emotionally abusive if true, not to mention downright stupid. But it was 2009, and it was Marilyn Manson. Age gap hysteria hadn’t set in, and Elliot Rodger hadn’t yet destroyed the idea that an angry white boy yearning for an uninterested woman might be romantic. Self-harm—or at least talking about self-harm—was ubiquitous in high schools, and generally, the perception was that if you were doing it, you yourself were the victim of a cruel world. The context doesn’t necessarily make all of the foregoing OK, but Manson was playing a role that we had all pre-approved and encouraged.

Where does context stop exonerating, and culpability begin? I argue that in the case of Manson it is murky. It’s not just that he is an easy scapegoat, although that is certainly part of it. The scapegoat is blamed for things he is innocent of, and while I believe this has happened to Manson at times, I also think that some of the more general flaws he is accused of are clearly accurate. I would never accuse Manson of being a nice guy or a good significant other (at least not during the era of the accusations). Setting the #MeToo stuff aside, his long list of disgruntled ex-bandmates proves he is at the very least “not a team player” and quite possibly just a prick by any reasonable metric. I always felt particularly bad for band cofounder and original guitarist Scott Putesky—AKA Daisy Berkowitz—who contributed to the band’s overall concept, and lent an iconic, Goth playing and composition style to Manson’s early work, but who acrimoniously exited midway through recording Antichrist Super after mistreatment and later filed a lawsuit for unpaid royalties15.

But isn’t there a bit of a “what else would you expect” dynamic with Manson regarding this? We like him partially because he is not a team player and because he is the dictator of his creative domain. The New Hampshire snot-blowing incident is another clear example of Manson just being an asshole that I won’t defend him on, other than to say that it was probably the result of substance abuse, and an authoritarian performance mindset, both of which Marilyn Manson just wouldn’t be Marilyn Manson without. I have met a few people who have interacted with Manson personally over the years and reviews have been mixed, with some people assuring me he is as wonderful as I would expect and some people saying he is as awful as I would expect. To me, he basically sounds like someone with a light and a dark side, who leans more one way or the other depending on context, and isn’t this 1) us all to an extent and 2) as advertised?

The murkiness of Manson’s culpability has to do with the hedonistic, contrarian role he chose for himself and for which the media and audiences have awarded him with much attention and money: the role of the “Born Villain” (as he would sum it up on his 2012 concept album by that same name). Manson defender Shane Cashman has compared Manson’s cultural role to that of the heyoka in Sioux culture: a “contrarian, jester, and satirist, who speaks, moves and reacts in an opposite fashion to the people around them” but ultimately towards socially and spiritually didactic end. Within popular culture one of Manson’s more obvious progenitors might be Oscar Wilde who was both a scapegoat and a socially beloved genuine and open “sinner”. This beloved-sinner dynamic is summed up well by Wilde in one of the many witticisms, spoken by Mephistophelian mouth-piece Lord Henry Wotton in The Picture of Dorian Gray:

“You will always be fond of me. I represent to you all the sins you never had the courage to commit.”

To wax a bit psycho-analytic: we like and maybe even need the Marilyn Mansons of the world because they shine a light on the unconscious drives of the id, providing them room to be exercised and observed (rather than quietly gathering power until they one day sneak up on us out of nowhere). His role in popular culture is like the character of Frank in Blue Velvet. We see an element of ourselves in him, which might be frightening, but in so doing we can better integrate our shadow:

Manson’s awareness of this role has grown throughout his career, starting in earnest perhaps with his post-Columbine reflections on Holy Wood, but revisited with more wisdom on his midlife output: 2009’s The High End Of Low (on which this dynamic is encapsulated best by Johnny Cash inspired track “Four Rusted Horses” and its refrain “everyone will come to my funeral to make sure that I stay dead”), 2012’s Born Villain (by way of the concept behind the whole record), 2015’s The Pale Emperor (featuring Manson’s further foray into outlaw-tinged blues and country, and perhaps most memorably of all: Manson’s identification of himself as the “Mephistopheles of Los Angeles”) and up to 2017’s Heaven Upside Down (which finds Manson still defiantly declaring “you say God and I say Satan” after so many years) and 2020’s We Are Chaos (featuring this relevant nugget of occult wisdom: “If you conjure the devil you better make sure you got a bed for him to sleep in” on standout track “Perfume”). It's easy for a lot of liberal-minded listeners to come to terms with the Satanic/ anti-Christian element of Manson’s shadow work, but perhaps harder for them to accept the sex-and-power-seeking element; yet both are critical pieces of the complete, anti-social package.

With Dorian Gray on the brain though: it’s not as if Manson has been spared the wear that comes with years of debauchery and villain status. Physically16, existentially, and spiritually he has not always aged gracefully. Manson has certainly hurt people, though, I’d posit that one of his biggest victims—well-illustrated by the cutting himself 158 times incident—has always been himself. My friend Alex Kazemi—who collaborated with Manson on an a series of unreleased IG spots for Heaven Upside Down —has a theory about Manson regarding Kabbalah and the concept of tzimtzum17: that around the time of the triptych Manson was purposely cultivating darkness which he intended to alchemize into light, but that this rebounded, leaving Manson stuck in the darkness, or perhaps even under the influence of dark entities. In support of this theory: the notorious Antichrist Superstar recording sessions in New Orleans, documented partially in The Long Hard Road Out of Hell, indeed involved excessive drug use, sleep deprivation, and self-harm, all while Manson was reading deeply on Kabbalah.

Esoteric concepts aside, it’s certainly the case—as mentioned previously—that Manson fell from certain creative and personal heights after Holy Wood and ultimately into an ostensible midlife crisis. This started first with Golden Age of Grotesque—an infectious pop-metal record, that nevertheless throws out a check-engine light for ennui when Manson rues on the opening line that “[e]verything has been said before, there's nothing left to say anymore”. It continued through the real-life turmoil of his divorce from Von Teese and affair-turned-relationship with Wood, culminating creatively with his two messiest (though I will argue not at all bad) albums Eat Me, Drink Me (2007) and The High End of Low (2009), and personally with virtually all of the bad behind-the-scenes behavior with women that is now the subject of the accusations against him. Dark energies rebounding may indeed have had something to do with it, though cocaine and absinthe abuse certainly played important supporting roles.

Indeed, maybe much of Manson’s trouble is just another story of substance abuse—an alcoholic and drug addict gone out of control—and the fact that he is now reportedly sober provides the most crucial step toward redemption. Substance issues don’t exonerate wrongdoing entirely in the public imagination, but most would accept that they add some nuance. I still favor the midlife crisis narrative as the overall narrative of the period: I view Manson’s substance abuse as symptomatic of his existential issues rather than the other way around. After all, it would be more than 10 years before he got sober for real, and seemingly his trajectory would go back upward well in advance of this. But my main point is that you can’t fully separate the ennui from the addiction in Manson’s case: that the severity of the issues was tightly correlated, and that we can talk about them in similar terms.

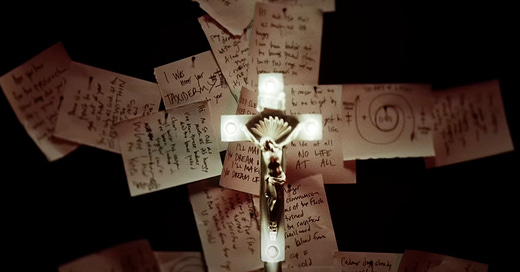

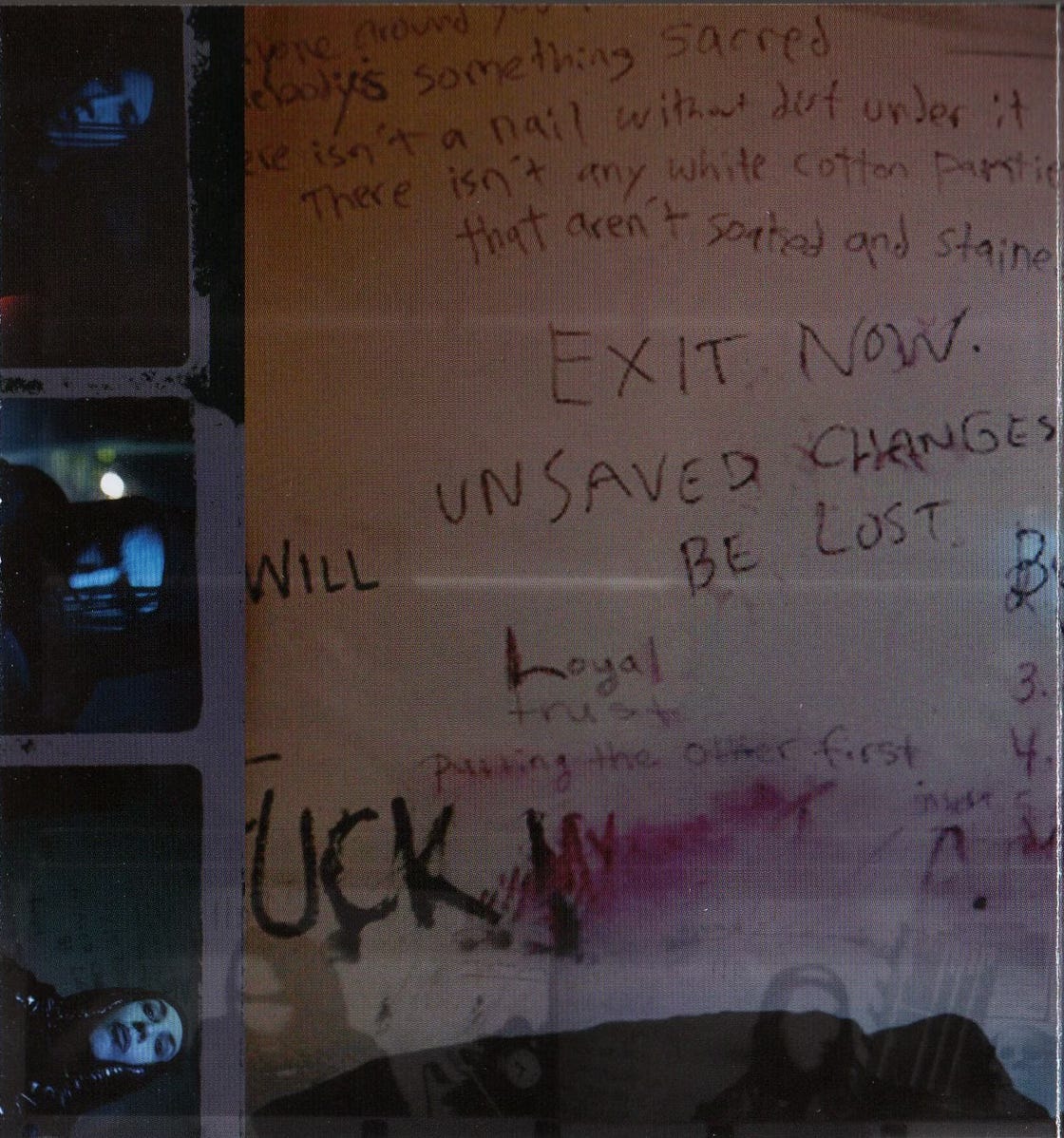

Various accusations against Manson run the duration of his career but it is easy to pinpoint the Evan Rachel Wood period—from roughly 2008-2010—as Manson’s “rock bottom” both in terms of substances and a more general emotional sadomasochism. During this period, Manson seemed content to be a magnet for, and dispenser of, pain and suffering. In the notorious Spin interview on The High End Of Low (of sledgehammer comment fame), Manson describes how he spent Christmas, 2008 alone with his “walls covered in scrawlings of the lyrics and cocaine bags nailed to the wall”. The liner notes of The High End Of Low later provided photographic evidence of this, and Manson would admit in retrospect:

“This was when I went insane, for real. I think I had a psychotic breakdown…[t]hose pictures of the crazy writing on my walls? That wasn’t for a photo shoot, that was how I lived at the time.”

Wes Borland—who is most famous as the guitarist for Limp Bizkit, but who also played with Manson from 2008-2009—claimed in 2021 that everything Manson is accused of is “true” and had this to say about his former bandmate: “he’s amazingly talented, but he’s fucked up and he needs to be put in check and he needs to get sober and he needs to come to terms with his demons…[h]e’s a bad fucking guy.” And this before recounting a story about Manson trying to choke him on stage. Borland might be conflating being an out-of-control asshole with being a criminal here, but it’s hard to dispute that Manson had demons he needed to come to terms with.

I expect 2008-2010 period is still something of a scar for Manson, or an open wound: the darkest and messiest period of his life, if not the worst. Doubtlessly Manson hurt women and other people in his life during this period (it’s just a question of to what extent the accusations are mired in opportunistic exaggeration, if they should be considered legal matters, etc.). It’s very possible he feels a degree of remorse for some of it now, though I expect his counsel has advised him to admit no guilt. One possible interpretation of all the facts at hand: I’m overcorrecting by arguing for Manson’s general innocence, and really this is the story of a decent guy with a bad side who became a bad guy with a decent side for a few years, and who should now pay the piper in some form or fashion. This would match the fact that his partners before and since the era have not made similar claims of abuse. If he was in the full throws of addiction and had something equivalent to a psychotic breakdown, who is to say?

But to return to the more general topic of midlife crisis, and the roots of this dark period: I would suggest that while Manson is far from an average Joe, the idea of dating a barely-legal actress like Evan Rachel Wood following his divorce— the dressing of the affair in literary Alice In Wonderland and Lolita references aside—was ultimately a pretty average Joe young-girlfriend-and-new-car type midlife crisis move. Wood’s HBO documentary Phoenix Rising treats us to all the hyperbolic ways Manson “love-bombed” her in the early days, most of which are no secret, as they match what Manson had always said himself about his relationship with Wood in interviews: statements about her creativity and rejuvenating charm helping him to rediscover the muse and fall in love not just with her, but with himself again.

I don’t want to add unnecessary insult to my general dismissal of Wood here, but looking at her work from the early 2000’s to now, one is tempted to say: really? What exactly was it that Manson saw in Wood other than an attractive young woman? A reasonably intelligent and creative young woman to be sure—but that level of muse and spiritual partner? The whole thing wreaks of a guy entering a mid-life crisis who needed to work certain things out for himself—personally and creatively—and ended up projecting quite a lot on a young woman, who happened to already have the reputation of temptress and Lolita from her filmography. My own impression from watching and reading interviews from this period is that Manson was not consciously “love bombing” Wood at all, and that, rather, he was entirely sincere in his view of her as a way out of his ennui. Manson is guilty of some lechery, to be sure, but perhaps a great deal more cringe.

The transition from youth to middle age is hard for anybody, and perhaps especially for the artist and the romantic. Operating without much of a life script—and with a certain Peter Pan syndrome endemic to the culture at large and the Rock N’ Roll world specifically—Manson went forward blindly. The role of prince of darkness—which had served him well up to that point, making him famous—indeed seemed to turn on him around this time. What was once a vehicle for self-expression became a vehicle of self-destruction. Taking a half-step back from this role might have been easier for Manson if he’d had the right sources of wisdom in his life or a self-transcending sense of purpose. The path to greater maturity is found by some in successful marriage and family, others by new projects or stoicism, but it is easy to simply miss the mark, and when something like the relationship with Wood fell through, it is easy to imagine how Manson fell to the depths of crazed, mid-life despair.

Tellingly, again in the notorious 2008 Spin Interview, Manson had this to say about getting back together with his long-term bassist Twiggy Ramirez (real name: Jeordie White) to record The High End of Low after Ramirez’s near 10-year absence:

“We both got ourselves into a lot of relationships that were probably unfair because of our lack of one another — we tried to have the girls in our lives fill a void that was missing in us as best friends... First and foremost, I’m married to what I do, every artist is. And I think that was something that didn’t make sense in my past relationship”.

Evidently, it’s easy enough for an artist to seek the muse in destructive places outside of the meat and potatoes of making art. It is also easy for an artist to use their naturally heightened appetites for pleasure and pain to fuck their life up between creative flow states. This seems to be what happened to Manson following his classic triptych of albums but before he again (in my estimation, at least) hit his stride in the 2010’s.

Born Villain (2012) is another record that Manson now says was hard to make—due to Twiggy falling on hard times—but interviews of the time found Manson ostensibly kicking off a new creative high: living and working out of the downtown LA apartment where he’d painted his first paintings, in a new relationship with photographer Lindsey Usich (whom he would stay with long term and later marry), and free for the first time since the early 90’s of the record label Interscope and it’s perceived limitations on his image and creativity, creating what Revolver referred to as his “freshest and most focused-sounding” work since Holy Wood. In an interview with Vanity Fair on the making of Born Villain, Manson reflected on a change in his creative philosophy following Eat Me Drink Me and The High End of Low:

“I was trying to make people feel what I was feeling—which wasn’t a good idea, especially because I was feeling like shit. Check mark number one: don’t do that. Don’t make records that make people feel bad.”

Born Villain was hailed as a comeback by many critics, and while it is not a top-tier Manson album in my book, it is easy to hear how Manson made a purposeful pivot back to high-energy Rock N’ Roll, no longer sacrificing great music and tight formalism for emotional directness. This pivot away from heavy emotionalism, as described by Manson in Vanity Fair, is interesting as it provides insight into his music-making process and supplies two useful vectors on which to rank his output. Manson’s best albums both express his inner state with emotional directness and do so in a slick, stylish, and well-crafted package. His original triptych—and hell, even his debut Portrait of An American Family (1994) in an angry-young-man sort of way—all achieve this double-task, as do two out of his last three albums (The Pale Emperor and We Are Chaos). Other albums like Born Villain, The Golden Age of Grotesque, and Heaven Upside Down achieve great stylistic and musical feats while—at least to me—feeling more emotionally distant (actually, I’d probably put Holy Wood in this category too, even though I know that is blasphemy). This leaves Eat Me Drink Me and The High End Of Low as his emotionally direct but stylistically messy albums, and while they are not the first albums I’d recommend to a new listener, I have a real soft spot for them, especially The High End of Low. All-in-all: 5-6 of Manson’s albums achieve both emotional directness and well-craftedness, 3-4 achieve just well-craftedness, and 2 achieve just emotional directness. Spoken like a true fan, though: I don’t think any of his albums achieve neither, and I feel confident in calling all of them good.

Evidently, I’m the sort of Manson listener who leans more toward the emotionally direct side of the equation, but doubtlessly Born Villain – with its return to form and fun—was every bit as necessary a step as Eat Me Drink Me and The High End of Low’s processing of emotion toward what may be my favorite overall Manson album, 2015’s The Pale Emperor, and the start of what I consider to be the second most fruitful run of his career.

When The Pale Emperor came out, I credited much of its greatness to Manson’s new collaboration with film and TV composer Tyler Bates, whom he’d met while working on Showtime’s Californication. To my mind, Manson had always been best at his most cinematic, mythologizing himself as a villain and outsider and Bates seemed to understand that sonically. Now Manson wasn’t only embodying the role of Born Villain but doing so with a cinematic universe to inhabit. Well not actually, but the grand, film-score-esque instrumentation opening tracks like “Killing Strangers” and “Warship My Wreck”, as well as TV-actor Walton Goggin’s preaching leading into "Slave Only Dreams to Be King" made it feel that way. The singles from this album: “Deep Six”, “Third Day of a Seven Day Binge”, “The Mephistopheles of Los Angeles”, “The Devil Beneath My Feet”, and “Cupid Carries a Gun” contain some of Manson’s catchiest hooks and are all shot through with a TV-Villain’s exuberance. The Pale Emperor is Manson’s bluesiest record—furthering the drift toward Americana its inherent outlaw connotations started by “Four Rusted Horses” —but also one of his most direct callbacks to early Goth and Glam influences. Manson no longer sounds concerned with projecting the image of the antichrist so much as simply embodying it, and the result feels simultaneously like his most adult album, and one of his catchiest and most fun.

Manson’s next collaboration with Tyler Bates, Heaven Upside Down (2017) would end up being a slightly more forgettable album for me, while his final pre-cancellation album We Are Chaos (2020) finds him replicating many of the virtues of The Pale Emperor with new collaborator Shooter Jennings, and so while I still have the utmost respect for Bates and think Manson’s choice to collaborate with him was one of the key positive pivots of his 2010’s career, I give most of the credit for the brilliance of The Pale Emperor to Manson himself: for getting back on his feet, his head seeming to finally clear after years of a more personal sort of darkness.

The Interviews with Manson from The Pale Emperor period certainly seem to find him on such an upward trajectory: drinking less (or having laid off absinthe specifically, at least), exercising more, reading Flannery O’Connor, Antonin Artraud, Baudelaire, and Faust, and spending more waking hours in the daylight after decades of a notoriously nocturnal lifestyle. Manson would continue this trajectory over the next half-decade, with the remainder of the 2010’s seeming to be a relatively calm and controversy-free period for him. Romantically, Manson also seemed to settle down and stabilize, marrying Usich in a private ceremony in 2020. He was doing much better by every metric and seemed a much more creative and much less destructive force in the world. But evidently, he had not quite outrun his demons for good.

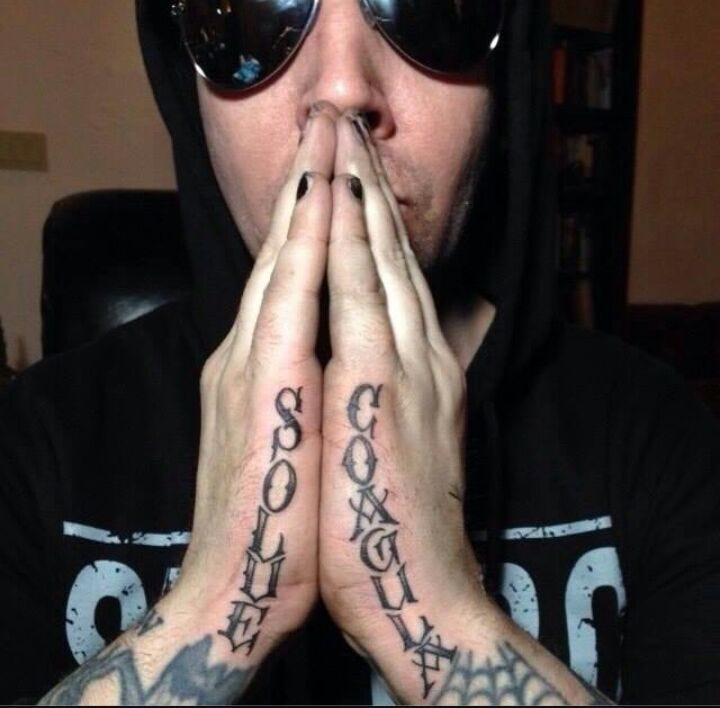

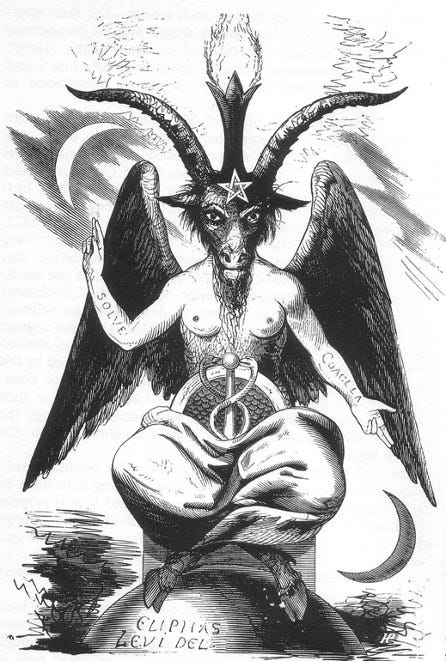

Around the time of The Pale Emperor Manson got the words SOLVE and COAGULA tattooed on opposite hands: a Latin alchemical formula meaning “dissolve and coagulate”, referring to the process of breaking something down to build it back stronger and more perfect: a critical part of the alchemical process of turning lower substances into higher substances. This is the idea of creation through destruction, and is related to the Kabbalistic idea mentioned earlier of converting darkness to light. While the formula is ultimately light-ward oriented, it shows up in some dark places, notoriously being emblazoned on the arms of Éliphas Lévi’s image of Baphomet (often mistaken for an image of Satan):

In Manson’s case, it would seem the process SOLVE COAGULA informs his creativity as well as psychology, epitomizing his purpose in embracing darkness and destruction in order to evolve.“Visit the interior parts of the earth,” goes another, related, alchemical maxim, “and by rectification you will find the hidden stone”. Needless to say: there are hazards to such an approach as SOLVE COAGULA, and one can become stuck in the brokenness. To the extent this has been Manson’s fate, he is perhaps aware of it, and SOLVE COAGULA also serves as the title of one of the greatest tracks on We Are Chaos, featuring the confessional refrain “I’m not special I’m just broken, and I don’t want to be fixed”. I didn’t start listening to We Are Chaos seriously until long after it came out, and over a year after Manson was canceled—in the fall of 2022, while starting work on The Black Album. I was floored by the whole album, but especially this line from SOLVE COAGULA. I thought: “if he never makes another record, this is one hell of a conclusion”. It struck me as confessional and perhaps even self-critical in a way I didn’t associate with Manson.

In the above-linked Revolver interview on The Pale Emperor, Manson reflects on his ambivalent relationship with religion and how it will always inform his work, whether he likes it or not. Referencing the new SOLVE COAGULA tattoo, Manson had this to say about the relation between music and religion, deeply relevant to both my exploration of Manson here, but the project of this whole book (deducing the spiritual influence of music on my life):

“The church wouldn't have tried to suppress music if there wasn't so much power in it. When you listen to a mass in Latin, it sort of hypnotizes you. When I was making this record, I got the Latin phrase "Solve et Coagula" tattooed on my hands, which refers to breaking something apart and putting it back together stronger. It's really all about alchemy in the end. It's about turning lead into gold, and that's what making music is. And they fear that—that's really the thing. It's not, "Oh, that evil rock and roll music— it makes the kids go out and have sex!" It's ‘They're stealing our market! Those are our customers! Give them back!’”

Manson’s interest in esotericism and magick predates his career, as The Long Hard Road Out Of Hell attests. His association with Anton Lavey is well documented, but Manson’s early lyrics especially reference Aleister Crowley, Jack Parsons and others. He is attracted to esotericism for, I expect, similar reasons to myself. Occultism, Gnosticism, Kabbalah, Alchemy and the rest of the Hermetic and esoteric traditions offer far more psychologically sophisticated views on the relation between darkness and light than does mainstream religion. Darkness is not the enemy of light but it’s necessary counterpoint and ally. So too with sin and virtue, chaos and order, destruction and creation, you name it: we must come to terms with one half of the equation in order to have the other. This is well encapsulated indeed by Levi’s Baphomet with one hand pointed up and one hand pointed down, bringing together the opposites: male and female, sun and moon, man and beast. It is also, of course, well reflected in that original dichotomy between “Marilyn” and “Manson”.

Call me evil, call me Luciferian, Freemason, or Illuminati but this picture of the opposing forces and the relation of their equilibrium to bliss, freedom, and human flourishing has always struck me as more accurate than the one provided by mainstream religion. I am basically conservative in most of my outlook, and yet I think the extent to which mainstream religion has (literally) demonized explorations of these dynamics is a testament to its deep-seated fears of the unknown, the power of expanding awareness, and maybe quite simply—as Manson alluded to in Revolver—the loss of audience. Even something as simple as the reduction of the pentagram—in its essence: a symbol representing man, highly relevant to Renaissance occultism and beyond—to an explicitly Satanic symbol reveals a fear of the recalibration of spirituality with science and empiricism—or at least lived-experience and individualism—as opposed to inherited dogma and tradition. Although there is a perception that “new age” has come and gone, I don’t think the West has fully realized the potential of this recalibration. Its results could indeed be revolutionary and counter to the interests of the powers that be, not just in religion but more generally. While I have cast my lot with this recalibration in certain regards, I am conservative enough to recognize its potential pitfalls: chaos may ensue before enlightenment, civilizationally as well as individually.

On the personal level, esotericism lacks a sufficient infrastructure to answer some of the more basic questions of how to live for those who partake in it: basic guidance for the path of life. Or rather: the esoteric traditions may have such guidelines, but they have been overlooked or cast aside by modern practitioners who have been granted access to the secrets without the necessity of discipline. Maybe this is the issue. Kabbalah, for instance, was traditionally the purview of married Jewish men over the age of 40 who had demonstrated learnedness in the Torah as well as sufficient piety—a far cry from 27-year-old Manson recording Antichrist Superstar—while Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, and various Eastern schools of esotericism have always been, and remain, protected by multiple walls of initiation. It is easy to see how someone like Manson—living his life based upon artistic and non-disciplined esoteric principles—might descend to the depths of The High End of Low era following such an unguided path. Even after what I consider to be a comeback in the 2010’s, it seems Manson found himself still “broken but not wanting to be fixed”, savoring the inherent energies and freedom of the SOLVE side of the equation, perhaps still hanging on to an older, broken identity. I am left with a sense that though Manson was able to outrun his demons for a number of years they finally caught up with him in 2021.

I don’t believe he will be convicted of anything vis-à-vis Evan Rachel Wood, but in many ways the process is the punishment. By seeming a cautionary tale, Manson joins Crowley, Parsons, and many other full-time occultists in harboring a fraught legacy. His enemies will keep calling him the devil, while even his defenders will admit his life was hectic, erratic, and/or marred by this mistake, that miscalculation, etc. But this is not the end of Manson’s story, and redemption may be nigh.

The recent buzz about Manson—starting with his appearance leading prayer at one of Kanye West’s Sunday services at the end of 2021 and continuing through 2024, where he has reappeared to us dramatically de-aged—is that he is sober, working on new material, and possibly that he has converted to Christianity. The rumors of his conversion to Christianity seem overstated—although, meaningfully, a spokesperson commented that Manson’s religious affiliation was “nobody’s business” after the Sunday Service. The sobriety and new music, however, have been confirmed.

At the time of writing this—evening of August 1st, 2024—new Manson music is expected imminently, and he is about to embark on a tour with Five Finger Death Punch and Slaughter To Prevail (two other metal acts that have found themselves variously on the outs with the left-leaning metal fanbase). I bought tickets last week to see Manson over Labor Day in Reno, Nevada. It will be the first—and quite possibly last—time I ever see Manson live. I am not much of a concert person, but the confluence of this particular show over a long weekend seems like a good time to make an exception. I will quite likely write an addendum to this piece on the show and the new music at a later point.

As for sobriety: it seems Manson completed his community service—ordered by the Judge of the New Hampshire snot blowing case—at a meeting place for Alcoholics Anonymous in Glendale, CA. Almost certainly, Manson has joined AA himself. I doubt he has converted to Christianity officially, but this does not mean he hasn’t “seen the light” or overcome himself in a more general way. If he has indeed joined AA, this would involve the central thrust of Christianity if not the dogma: a true and thorough surrender to a higher power. From what we have seen of his forthcoming work thus far, Manson seems to have struck a balance, remaining an alchemical man, but with a newfound reverence. If he made his peace with the Devil long ago, maybe he has now finally made peace with God. Only time will tell, but I cannot help but root for him.

I.e. the member of Blood on The Dancefloor who is not a confirmed pedophile.

Getting more into Manson came pretty immediately along with also getting into more “mature” goth and alternative influences: Bowie, The Cure, Joy Division, The Doors, the first waves of Punk and Post-Punk in general.

On Alice In Wonderland: allow me to admit to my self-declared “cringiest memory” that transpired in early March of 2010, just a few weeks after listening to “Great Big White World”. This memory is also an illustrative example of some of the half-steps I took at first to try to integrate my new interests and views in with my old social group. Serendipitously, at just the moment I was becoming newly interested in Alice In Wonderland, Tim Burton’s Disney adaptation was due in theaters, and starring Manson’s buddy Johnny Depp as the Mad Hatter no less. Here was a great opportunity to experience some real culture in a way that my mall-rat friends and girlfriend would also be able to vibe with.

I had the idea that we should all dress up for opening weekend. In 2010 it would have been normal enough, if dorky, to do this for a Harry Potter movie. The fact that we did it for Alice In Wonderland and that it was my idea, however, is mortifying. My girlfriend was the Queen of Hearts, while I was the King of Hearts (who is hardly even a character, I know), thankfully not wearing anything more elaborate than a cape. My girlfriend and I had a fight not long into the movie when she wouldn’t stop talking, distracting me from what I was trying to appreciate as an art-house cinema experience. Needless to say, nothing went as planned in terms of cultural enrichment. I still think this Burton adaption of Alice could have been decent, but man was it hot garbage.

Not that it was by any means all innocent. My Ian Curtis fetishism would peak with watching the Anton Corbijn biopic Control and getting inspired by the pill-drawer raiding scene to try to seek out my own home high, terminally deprived as I was of weed and whatever other drugs can be found in high schools. And so my first drug experience was off 9 or so pink Benadryl capsules. Diphenhydramine in high doses is a notoriously unpleasant deliriant, but at the relatively low dose I took, the effect was mainly a profound sleepiness and an auditory hallucination of a long, slowed-down version of instrumental Joy Division track “Incubation”. In the 2020’s, recreational Benadryl usage has led to an ill-fated TikTok challenge, and a (I think only semi-serious) Subreddit, notorious for spawning a creepy pasta claiming that heavy users can consistently conjure a shadow entity known as “the hat man” in their delirium. Not recommended.

Culminating with the fact that Manson made his own Tarot deck to be released in promotion of Holy Wood but present as early as Antichrist Superstar, the first cycle” of which is called “The Hierophant”. To sketch out the Manson/Tarot connection: the Major Arcana of the Tarot tell the story of “The Fool’s Journey”—a story of personal evolution and the path through life—that begins where it ends in a positive sense: the Fool encounters each archetype and integrates them into his self-understanding, culminating with his re-entry into the world as a wiser man (yet still fundamentally the fool and ready for subsequent journeys). Manson’s triptych storyline is a bleak reflection of this, mirroring the notion of cyclical evolution, but with a distinct pessimism. In Manson’s case an anguished young man, “the worm” grows up to be a superstar and ultimately a self-destructive fascistic leader.

Most obviously by way of the protagonist of Holy Wood bearing the name Adam Kadmon, but the symbolism of Kabbalah and Tetragrammaton are ubiquitous throughout the packaging and booklets for both Holy Wood and Antichrist Superstar, which are quite elaborate and worth checking out. The Antichrist Superstar booklet in particular is a rabbit hole of dark, mystical symbolism in its own right, well-explained in this vintage fan post.

Jodorowsky who was at one point a friend of Manson’s, read his Tarot on several occasions, and even officiated his “alchemical” wedding to Dita Von Teese in 2005. The marriage was unfortunately not quite as auspicious or binding as the language of Jodorowsky’s ritual, only lasting one year.

Synonymous with the image of the Dying God of the old aeon, or “Hanged Man” in the language of the tarot and related to Manson’s focus on Lennon/JFK martyrdom on the album as well.

A final note on the album, and Manson’s artistry: The Valley of the Shadow of Death versus Holy Wood thing is itself a direct homage Charles Manson, who promised to hide his followers in Death Valley to ride out the race war they were trying to commence back in Los Angeles. (Marilyn) Manson himself traveled between recording studios in Laurel Canyon and Death Valley to try and capture the aesthetic of the contrast between LA and the desert. Say what you will about Manson but not that he didn’t fully commit to his artistic choices.

I say deservedly because the album is really fucking good, in a way both myself and the hip/progressive music press could appreciate. We Are Chaos finds Manson teaming up with Shooter Jennings—son and torch-carrier of Outlaw Country pioneer Waylon Jennings—and leaning into some of his best artistic instincts: toward glam rock, goth-tinged country, and ruminations on violence, terminal villain status, and alchemy.

Some would say Manson’s cancellation is comeuppance for making a covenant with such liberal moralizers, though I can take no schadenfreude for reasons of perceived indebtedness already discussed. And besides: 2020 was a weird year for all of us.

Uncovered as part of an only tangentially related, but not exactly flattering-to-Wood’s-trustworthiness custody battle with ex Jamie Bell, that ended in the latter receiving near full custody.

A professional activist, artist, and rabble-rouser with her own questionable reputation, whose involvement in this case runs deep.

He also died of colon cancer in 2017 at the age of 49, which sucks.